Singapore recently celebrated its National Day: every residents’ association spent July providing decorations and bunting and exhorting residents to deck their parapets with ordered rows of red-and-white flags. There was a parade, rehearsed for weeks beforehand, and by the time it took place the novelty of the aircraft and the fireworks must have worn off, though you wouldn’t have known it from the applause. I really enjoyed it. Here’s a video:

(A week later they hosted the Youth Olympic Games opening ceremony. Watch the last three minutes or so: amazing set, Speer-like, shades of Metropolis, drifting in the half-shadow of Marina Bay, a place that’s no less artificial or considered than a stage)

This sort of thing is a reminder that in lots of ways Singapore is a made-up country, one created suddenly and with a sense of urgency only a generation or so ago. The patriotism that is encouraged here is genuine, of course, and there are very real threats to the island’s security which demand a sense of loyalty, but there’s an untested quality to it that draws your attention to the way it’s been made up, in schools and workplaces and televised events.

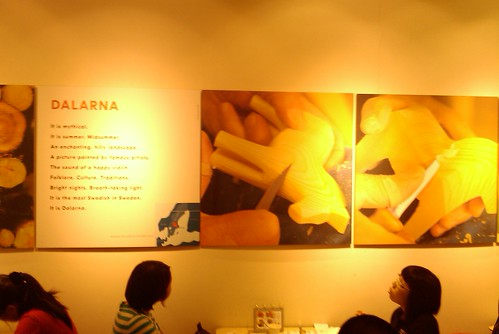

They make up other countries as well. These pictures were taken in the IKEA cafeteria, after eating meatballs and boiled potatoes.

“Dalarna. It is mythical. It is summer. Midsummer. An enchanting hilly landscape. A picture painted by famous artists. The sound of a happy violin. Folklore. Culture. Traditions. Bright nights. Breath-taking light. It is the most Swedish in Sweden. It is Dalarna.”

Sweden, mystical home of sensible interior planning and refreshing attitudes to public bathing. Of course, we do the same thing, and not just to Sweden: there’s a distance of a couple of thousand miles at which any country is more easily understood through the ways it’s made up than through any actual experience. People in the UK did it with various countries now in the Commonwealth, Americans did it with Japan, and now Singaporeans romanticise Northern European countries and the parts of the culture they like. The Swiss are used in a similar way: the highest quality butchers, embroiderers, dry cleaners and health food suppliers all have “Swiss” in their name. The British aren’t treated the same way, being a much more real part of recent history here.

None of this is a criticism. But all this making up other countries has made it more obvious to me how I choose the parts of England that I miss, how I make up my own country to be nostalgic about. Since I arrived I’ve been listening to Dave Swarbrick and Alistair Anderson, and to groups that imagine their own village more obviously: the Moon Wiring Club, Belbury Poly, the Focus Group and others on the Ghost Box label. When I miss home now, after watching other people construct their own ideas of countries, I feel much more aware that I’m missing somewhere I made up, and take more pleasure in populating it on purpose: old Children’s Film Foundation programmes, Greater London Council lettering on country roadsigns, AA badges, muted, textured countryside, Puffin books and Alan Garner countrysides, morris dancing, public works in rollling hills from Dacorum and Milton Keynes borough councils, long barrows and neolithic landscapes, greaseproof paper and boxes of orange juice, whimsical acts of principled civil disobedience, well-spoken male voices in children’s radio programmes, village flotsam from the Festival of Britain, electronic engineering, and further away the Channel and the North Sea and stories of smuggling and secrecy.